Galip nut, Java almond

A tropical plant. The galip (Canarium indicum) grows in coastal areas, and is most common in the islands such as North Solomons Province, New Britain and New Ireland. It also occurs naturally in the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Guam. It occurs on the New Guinea mainland and Papua as well as in Maluku in Indonesia. It has been taken to some other countries to grow. Galip nuts are common in the lowland rainforest. It suits humid locations. They mostly grow from sea level up to about 450 m altitude in the equatorial tropics but can be up to 900 m above sea level.

Also known as:

Angai, Angari, Hinuei, Jal, Jangli badam, Java badami, Kagli mara, Kanari, Keanee, Kenari, Kenari ambon, kenari bagea, Lawele, Nangai, Nanghai, Ngali, Ngari, Ngi, Ngoeta, Nolepo, Nyia nyinge, Nyia Nyinge, Okete, Pili, Pohon kenari jawa, Pohon kenari merah, Rata kekuna, Sela, Voi’a, Waknga

Synonyms

- Canarium amboinense Hochr.

- Canarium commune L.

- Canarium grandistipulatum Lauterb.

- Canarium mehenbethene Gaertner [Illegitimate]

- Canarium moluccanum Blume

- Canarium nungi Gillaumin

- Canarium shortlandicum Rechinger

- Canarium subtruncatum Engl.

- Canarium zephyrinum Rumph. ex Blume

Edible Portion

- Nuts, Seeds - oil

Where does Galip nut grow?

Found in: Africa, Asia, Australia, Bougainville, East Timor, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hawaii, Indonesia, Malaysia, Micronesia, Myanmar, Niue, Pacific, Palau, Papua New Guinea, PNG, Philippines, Pohnpei, Samoa, SE Asia, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Tahiti, Timor-Leste, Tonga, United States, Vanuatu

Notes: There are 80-95 Canarium species. Galip nuts Canarium indicum Names. In Tok Pisin the word “galip” can be used in several different ways. It has both a general and then also a specific meaning. It can be used very widely to include many nuts such as peanuts, pao nuts, and several other nuts from trees. As the word “galip” was originally a Tolai word from the Kuanua language this is the way it is being used in this article. Tolais used “galip” for the nuts of a particular tree which is also called the Canarium almond in English. Scientists give every plant a scientific name in the Latin language, then it is the same for all scientists of the world, no matter what language they speak. The name scientists have given to this plant is Canarium indicum. It was given this name by a man called Linnaeus as long ago as 1759. Unfortunately early scientists mixed up two similar nut trees and so the scientific names have also got mixed up and are often used incorrectly. The correct name for the common galip in Papua New Guinea is Canarium indicum L. A similar, but different, nut tree grown in Malaysia and in Pacific Island countries such as Fiji, is called Canarium vulgare Leenhauts. A name which has been used incorrectly for both these plants is Canarium commune L and this name should no longer be used. The way to tell the difference between these 2 plants is by looking at a leafy type of growth (called a stipule) which occurs near where the leaf stalk joins the branch. In the PNG galip (C. indicum ) this leafy part stays on the stalk and around the edge of it, there are teeth like a saw. In the Pacific tree (C. vulgare ) this leafy stipule has a smooth edge and also tends to drop off the tree quickly. This group of plants called Canarium were given this part of their name after a Malayan word “kanari” which was used for these plants. There are about 100 different species of plants belonging to this group called Canarium. All of these plants originally occurred only in a few countries of the world, mostly in the Asia and Pacific area. The area is shown on this map drawn by a botanists called Leenhauts who has made a special study of these plants. A few of these plants also occur in Africa. Within the Canarium genus or group, there are several different plant species which produce edible nuts. The ones that occur in Papua New Guinea and have nuts which are eaten are listed below. Canarium indicum L - common galip or galip tru Canarium salomonense ..urtt Canarium kaniense Laut Canarium schlechteri Laut. There is also probably a species in the Western Province of which the flesh is eaten, after cooking, like the Chinese olives (Canarium album ). It is interesting that such a large and important group of food plants has not been studied and improved by agriculturalists. The next table is of the different scientific names of the edible Canarium plants known from other countries. Canarium album Raeusch Canarium amboinensis Hochr. Canarium australasicum Canarium bengalense Rozb. Canarium decumanum Gaertn. Canarium denticulatum Blume Canarium grandiflorum Benn Canarium littorale Blume Canarium luzonicum A Gray Canarium megalanthum Merr. Canarium muelleri Canarium nigrum Engl. Canarium nitidum Benn Canarium odontophyllum Miqu. Canarium oleosum (Lamk.)Engl. Canarium ovatum Engl. Canarium patentinervium Miqu. Canarium polyphyllum K.Schum. Canarium pseudo-decumanum Hoohr. Canarium purpurascens Benn. Canarium rufum Benn. Canarium samoense Engl. Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. Canarium secundum Benn Canarium strictum Roxb. Canarium sylvestris Gaertn. Canarium vulgare Leenh. Canarium williamsii C.B.Rob. Canarium zeylanicum Blume What is a galip nut tree like? It is a large tree often up to 40m high. The stems are often twisted or rough and there are usually buttresses at the base of the tree. The small branches are more or less powdery. If a small branch is cut crossways and looked at very carefully, small round vascular strands can be seen in the pith or centre mass of cells. (This is different to most woody trees where these are in a more or less continuous circle around the edge of the branch). The leaf of a galip tree is made up of 3 to 7 pairs of leaflets. The leaves do not have hairs on them. The leaflets are oblong and can be 7 to 28 cm long and 3 to 11 cm wide. At the base of a leaf where the stalk joins the branch there is a special leaf like structure that is important for helping to identify the PNG galip tree. This leafy structure is called a stipule and it is large and has saw like teeth around the edge. (Another PNG Canarium nut (C. kaniense ) also has a similar large stipule.) The flowers are mostly produced at the end of the branches. A group of flowers are produced on the one stalk. The flowers are separately male and female. The male flowers have 6 anthers or pollen containers in a ring. In the female flower these 6 stamens are improperly developed (staminodes) around a 3 celled ovary. The galip fruit has 3 cells (sometimes 4) but mostly only one cell is fertile so that 2 of the cells are empty, and one has a kernel. Where do galip nuts grow? The galip (C. indicum ) grows in coastal areas, and is most common in the islands such as North Solomons Province, New Britain and New Ireland. It also occurs naturally in the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Guam. It occurs on the New Guinea mainland and Irian Jaya as well as in Maluku in Indonesia. It has been taken to some other countries to grow. Galip nuts are common in the lowland rainforest. They mostly grow from sea level up to about 300 m altitude. How do you grow galip nut trees ? Many of the galip nuts take several months for the seeds to start to grow. As well, the seeds normally should not be buried under the ground, but should be just near the surface of the ground. Care is needed to see that the seeds and seedlings do not dry out. As the seed grows or germinates, a well defined cap is split off the nut. Trees grow fairly quickly. Varieties of galip nuts ? Not all galip nuts are the same. People on the St Matthias group of islands off New Ireland recognise 7 different kinds. These include the most common pale coloured galip but also one with a reddish black seed, one with a larger kernel, one with a small kernel, one with a round fruit and one with a thin walled nut. This sort of variation is important for plant breeders who want to improve the kinds that are grown. People who have talked briefly about galip nut growing and use in villages. Blackwood,B., 1935, Both sides of Buka Passage. Oxford. page 278-280. Connell,J., 1977, Hunting and Gathering: the forage economy of the Siwai of Bougainville. Australian National University Development Studies Centre Occasional Paper No 6 pages 11-13. Guppy,H.B., 1887, The Solomon Islands and their Natives, London. Ogan,E., 1972, Business and Cargo: socio-economic change among the Nasioi of Bougainville. New Guinea Research Bulletin No 44 Canberra. Pages 37, 131. Oliver,D.L.,1955, A Solomon Island Society: Kinship and Leadership among the Siwai of Bougainville. Beacon. pages 28, 298, 311, 344- 347. Parkinson,R.F.,1907, Thirty Years in the South Seas., Stuttgart. (English trans. N.C.Barry) p438 Ross,H.M.,1973, Baegu. Social and ecological organisation in Malaita, Solomon Islands. Illinois Studies in Anthropology No. 8 Urbana p43. Scheffler,H.W., 1965, Choiseul Island Social Structure, Berkley and Los Angeles p4. Botanists who have helped describe and name galip nut trees. Havel,J.J.,1975, Forest Botany Vol 3 Part 2 Botanical Taxonomy PNG Dept. Forests p126 Johns,R.J.,1976, Canarium. in Common Forest Trees of PNG Part 5 p191 Forestry College, Bulolo. Leenhauts,P.W.,1955, Canarium on the Pacific. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 216. Leenhauts,P.W.,1955, Florae Malesianae Precursors XI New Taxa in Canarium. Blumea 8(1):184- Leenhauts, P.W., 1955, Flora Malesiana ser 1 Vol 5(2):249-327 Leenhauts, P.W., 1959, Blumea 9 :275 - 475. Peekel, An Illustrated Flora of the Bismarck Archipelago

Status: It is a cultivated food plant. Moderately common and popular in coastal and island areas in Papua New Guinea.

Growing Galip nut, Java almond

Cultivation: Trees are planted near houses. They are mostly grown from seed. Many of the galip nuts take several months for the seeds to start to grow. As well, the seeds normally should not be buried under the ground, but should be just near the surface of the ground. Care is needed to see that the seeds and seedlings do not dry out. As the seed grows or germinates, a well defined cap is split off the nut. Trees grow fairly quickly. They can be grown by budding or grafting. Considerable varietal variation occurs.

Edible Uses: The kernels are eaten raw or slightly roasted. Seeds can be dried and stored. The nuts can be pressed for oil. The fresh oil is mixed with food. CAUTION The seed coat should not be eaten as it carries some substance producing diarrhoea.

Production: Trees flower after 5-7 years. Fruit reach maturity 5-8 months after flowering. The main season is often April to May but trees can bear nuts 2 or 3 times a year. An average kernel weighs 3 g. A mature tree can produce 100 kg of nuts which results in 15 kg of kernels. Climbing the large trees is difficult and dangerous, so often nuts are harvested after they fall. Nuts are often stored inside houses after the fleshy outer layer is removed but the hard shell remains. Nuts which are removed from the shell and roasted can be stored in sealed containers for many months. The nuts are often coarsely ground and added to other foods.

Nutrition Info

per 100g edible portion| Edible Part | Energy (kcal) | Protein (g) | Iron (mg) | Vitamin A (ug) | Vitamin c (mg) | Zinc (mg) | % Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuts | 461 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 14 | 8 | 2.4 | 35 |

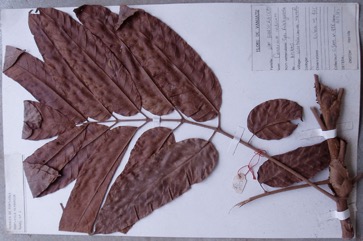

Galip nut, Java almond Photos

References

Galip references

ACIAR, 2012, Canarium Nut Value Chain Review

Altschul, S.V.R., 1973, Drugs and Foods from Little-known Plants. Notes in Harvard University Herbaria. Harvard Univ. Press. Massachusetts. no. 1981

Ambasta S.P. (Ed.), 2000, The Useful Plants of India. CSIR India. p 100 (As Canarium commune)

Amoen. acad. 4:143. 1759

Arora, R. K., 2014, Diversity in Underutilized Plant Species - An Asia-Pacific Perspective. Bioversity International. p 93 (Also as Canarium commune and Canarium moluccanum)

Barrau, J., 1976, Subsistence Agriculture in Melanesia. Bernice P. Bishop Museu, Bulletin 219 Honolulu Hawaii. Kraus reprint. p 53 (As Canarium commune and Canarium nungi and Canarium mehenbethene)

Barrau, J., 1976, Subsistence Agriculture in Polynesia and Micronesia. Bernice P. Bishop Museu, Bulletin 223 Honolulu Hawaii. Kraus reprint. p 56 (As Canarium commune)

Bircher, A. G. & Bircher, W. H., 2000, Encyclopedia of Fruit Trees and Edible Flowering Plants in Egypt and the Subtropics. AUC Press. p 78 (As Canarium amboinense and Canarium commune)

Blackwood, B., 1935, Both sides of Buka Passage. Oxford. page 278-280.

Borrell, O.W., 1989, An Annotated Checklist of the Flora of Kairiru Island, New Guinea. Marcellin College, Victoria Australia. p 60, 100+7, 180

Bourke, R. M., Altitudinal limits of 230 economic crop species in Papua New Guinea. Terra australis 32.

Bremness, L., 1994, Herbs. Collins Eyewitness Handbooks. Harper Collins. p 41

Brouk, B., 1975, Plants Consumed by Man. Academic Press, London. p 222 (As Canarium commune)

Brown, Useful Plants of the Philippines. p 244

Bourke, M., 1995, Edible Indigenous Nuts in Papua New Guinea. In South Pacific Indigenous Nuts. ACIAR Proceedings No 69, Canberra. p 46

Burkill, I.H., 1935, Canarium A dictionary of the economic products of the Malaya Peninsula. Vol 1 pp 430-437. London Cown Agents.

Burkill, I.H., 1966, A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Vol 1 (A-H) p 433 (As Canarium commune)

Cabalion, P. and Morat, P., 1983, Introduction le vegetation, la flore et aux noms vernaculaires de l'ile de Pentcoste (Vanuatu), In: Journal d'agriculture traditionnelle et de botanique appliquee JATBA Vol. 30, 3-4

Clarke, W.C. & Thaman, R.R., 1993, Agroforestry in the Pacific Islands: Systems for sustainability. United Nations University Press. New York.

Connell, J., 1977, Hunting and Gathering: the forage economy of the Siwai of Bougainville. Australian National University Development Studies Centre Occasional Paper No 6 pages 11-13

Corner, Kedondong family Burseraceae. p177-178

Coronel, R.E., 1982, Fruit Collections in the Philippines. IBPGR Newsletter p 9 (As Canarium commune)

Darley, J. J., 1993, Know and Enjoy Tropical Fruit. P & S Publishers. p 78

Elevitch, C.R.(ed.), 2006, Traditional Trees of the Pacific Islands: Their Culture, Environment and Use. Permanent Agriculture Resources, Holualoa, Hawaii. p 209

Evans, B. R, 1999, Edible nut Trees in Solomon Islands. A variety collection of Canarium, Terminalia and Barringtonia. ACIAR Technical Report No. 44 96pp

Facciola, S., 1998, Cornucopia 2: a Source Book of Edible Plants. Kampong Publications, p 62 (As Canarium commune)

Flora of Solomon Islands

Flowerdew, B., 2000, Complete Fruit Book. Kyle Cathie Ltd., London. p 245 (As Canarium commune)

French, B.R., 1986, Food Plants of Papua New Guinea, A Compendium. Asia Pacific Science Foundation p 163

French, B.R., 2010, Food Plants of Solomon Islands. A Compendium. Food Plants International Inc. p 164

Fruct. sem. pl. 2:98, t. 102. 1790 (As Canarium mehenbethene)

Furusawa, T., et al, 2014, Interaction between forest biodiversity and people’s use of forest resources in Roviana, Solomon Islands: implications for biocultural conservation under socioeconomic changes. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2014, 10:10

Guppy, H.B., 1887, The Solomon Islands and their Natives, London.

Havel, J.J., 1975, Forest Botany, Volume 3 Part 2 Botanical taxonomy. Papua New Guinea Department of Forests, p 126

Hedrick, U.P., 1919, (Ed.), Sturtevant's edible plants of the world. p 148

Henderson, C.P. and I.R. Hancock, 1988, A Guide to the Useful Plants of the Solomon Islands. Res. Dept. Min of Ag. & Lands. Honiara, Solomon Islands. p 66

Jardin, C., 1970, List of Foods Used In Africa, FAO Nutrition Information Document Series No 2.p 32 (As Canarium commune)

Johns, R.J.,1976, Canarium. in Common Forest Trees of PNG Part 5 p 191 Forestry College, Bulolo

Kiple, K.F. & Ornelas, K.C., (eds), 2000, The Cambridge World History of Food. CUP p 1792 (As Canarium commune)

Lebot, V. & Sam, C., Green desert or ‘all you can eat’? How diverse and edible was the flora of Vanuatu before human introductions?. Terra australis 52 p 410

Leenhouts, P.W., 1955, Canarium on the Pacific. Bernice P.Bishop Museum Bulletin 216. p 26

Leenhouts, P.W., 1955, Florae Malesianae Precursors XI New Taxa in Canarium. Blumea 8(1):184-

Leenhouts, P.W., 1955, Flora Malesiana ser 1 Vol 5(2):249-327 p 266 (As Canarium mehenbethene)

Leenhouts, P.W., 1959, Blumea 9 :275 - 475.

Leenhouts, P.W., 1955, Canarium on the Pacific. Bernice P.Bishop Museum Bulletin 216. p 27 (As Canarium nungi); (As Canarium mehenbethene)

Lepofsky, D., 1992, Arboriculture in the Mussau Islands, Bismarck Archipelago. Economic Botany, Vol 46, No. 2, pp. 192-211

Massal, E. and Barrau, J., 1973, Food Plants of the South Sea Islands. SPC Technical Paper No 94. Nounea, New Caledonia. p 32 (As Canarium nungi)

Menninger, E.A., 1977, Edible Nuts of the World. Horticultural Books. Florida p 27 (As Canarium commune)

Menninger, E.A., 1977, Edible Nuts of the World. Horticultural Books. Florida p 27 (As Canarium nungi)

Menninger, E.A., 1977, Edible Nuts of the World. Horticultural Books. Florida p 27

Milow, P., et al, 2013, Malaysian species of plants with edible fruits or seeds and their evaluation. International Journal of Fruit Science. 14:1, 1-27

Moon, H. K., et al, 2010, Tropical Tree of Indonesia. Korea Forest Research Institute. p 44

Ogan, E., 1972, Business and Cargo: socioeconomic change among the Nasioi of Bougainville. New Guinea Research Bulletin No 44 Canberra. Pages 37, 131

Oliver, D.L.,1955, A Solomon Island Society: Kinship and Leadership among the Siwai of Bougainville. Beacon. pages 28, 298, 311, 344- 347

Owen, S., 1993, Indonesian Food and Cookery, INDIRA reprints. p 68

Parkinson, R.F.,1907, Thirty Years in the South Seas., Stuttgart. (English trans. N.C.Barry) p 438

Peekel, P.G., 1984, (Translation E.E.Henty), Flora of the Bismarck Archipelago for Naturalists, Division of Botany, Lae, PNG. p 281, 280

Powell, J.M., Ethnobotany. In Paijmans, K., 1976, New Guinea Vegetation. Australian National University Press. p 108

Priyadi, H., et al, 2010, Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java. A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use. CIFOR, FFPRI, SLU p 9

Ross, H.M.,1973, Baegu. Social and ecological organisation in Malaita, Solomon Islands. Illinois Studies in Anthropology No. 8 Urbana p 43.

Scheffler,H.W., 1965, Choiseul Island Social Structure, Berkley and Los Angeles p 4.

Smith, A.C., 1985, Flora Vitiensis Nova: A New flora of Fiji, Hawai Botanical Gardens, USA Vol 3 p 473

Soepadmo, E. and Wong, K. M., 1995, Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak. Forestry Malaysia. Volume One. p 48

Solomon, C., 2001, Encyclopedia of Asian Food. New Holland. p 191

Staples, G.W. and Herbst, D.R., 2005, A tropical Garden Flora. Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, Hawaii. p 207

Sukarya, D. G., (Ed.) 2013, 3,500 Plant Species of the Botanic Gardens of Indonesia. LIPI p 177

The Pacific Islands Food Composition Tables http://www.fao.org/docrep No F072

USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN). [Online Database] National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. Available: www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/econ.pl (10 April 2000)

Verheij, E. W. M. and Coronel, R.E., (Eds.), 1991, Plant Resources of South-East Asia. PROSEA No 2. Edible fruits and nuts. Pudoc Wageningen. p 320

Walter, A & Sam, C., 1995, Indigenous Nut Trees in Vanuatu: Ethnobotany and Variability. In South Pacific Indigenous Nuts. ACIAR Proceedings No 69. Canberra. p 57

Walter, A. & Sam C., 2002, Fruits of Oceania. ACIAR Monograph No. 85. Canberra. p 131

Wickens, G.E., 1995, Edible Nuts. FAO Non-wood forest products. FAO, Rome. p 59, 111

World Checklist of Useful Plant Species 2020. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

www.pngplants.org

www.worldagroforestrycentre.org/treedb/